Regular internet stalkers will have spotted that nearly 3 weeks ago I made a very big move across the Atlantic to start a new role as Deputy Provost with Athabasca University. I’ve based myself in Edmonton, on the basis that I at least know 1 person here, and am slowly finding my feet. I’ve never been a foreigner. I’ve never had anything less than an absolute right to remain in a country, so this is all a new and not a little sobering experience (and for friends back home affected by Brexit, I still don’t think I understand even a fraction of how stressful things must be). One of the things I am acutely aware of is that I’m not the first Scot to make the trip in this direction in order to seek their fortunes. So I need to think carefully about where I am. Indeed there are lots of little boxes in social media and other places where it demands that I update my “Location”.

When I write my address down, I’m in the city of Edmonton…

“By 1795, Fort Edmonton was established on the river’s north bank as a major trading post for the Hudson’s Bay Company. The new fort’s name was suggested by John Peter Pruden after Edmonton, London, the hometown of both the HBC deputy governor Sir James Winter Lake, and Pruden.” (Edmonton, Wikipedia)

…in the province of Alberta…

“Alberta was named after Princess Louise Caroline Alberta (1848–1939), the fourth daughter of Queen Victoria” (Alberta, WIkipedia)

…in a country called Canada…

“While a variety of theories have been postulated for the etymological origins of Canada, the name is now accepted as coming from the St. Lawrence Iroquoian word kanata, meaning “village” or “settlement”. In 1535, Indigenous inhabitants of the present-day Quebec City region used the word to direct French explorer Jacques Cartier to the village of Stadacona. Cartier later used the word Canada to refer not only to that particular village but to the entire area subject to Donnacona (the chief at Stadacona); by 1545, European books and maps had begun referring to this small region along the Saint Lawrence River as Canada.” (Canada, Wikipedia)

I’m limited at present in the tools at my disposal for thinking about this. I’m culturally rooted somewhere else and that’s going to be my immediate go-to place; in time I will change that, but today I need to work with what I’ve got so bear with me….

Robert MacFarlane’s magical book Landmarks was spurred into creation by the news that many words used to describe the natural world had been dropped from the Oxford Children’s Dictionary in favour of other words deemed more relevant to modern life.* Although focussed on exploring the words used to describe the landscape of the British Isles, the intimate relationship he describes between language, sense of place, and sense of self I think transcends any one territory:

“Words act as compass; place-speech serves literally to enchant the land – to sing it back into being, and to sing one’s being back into it.”

In Alice Through the Looking Glass Alice encounters the “Wood Where Things Have no Names” and in that experience comes to understand that the power to name things is not simply about labelling, but also controls how things operate in the world in relation to other things. When the power to remember and use names is gone, the world is a disconcerting and disconnected place, in which the natural order of things is subverted.

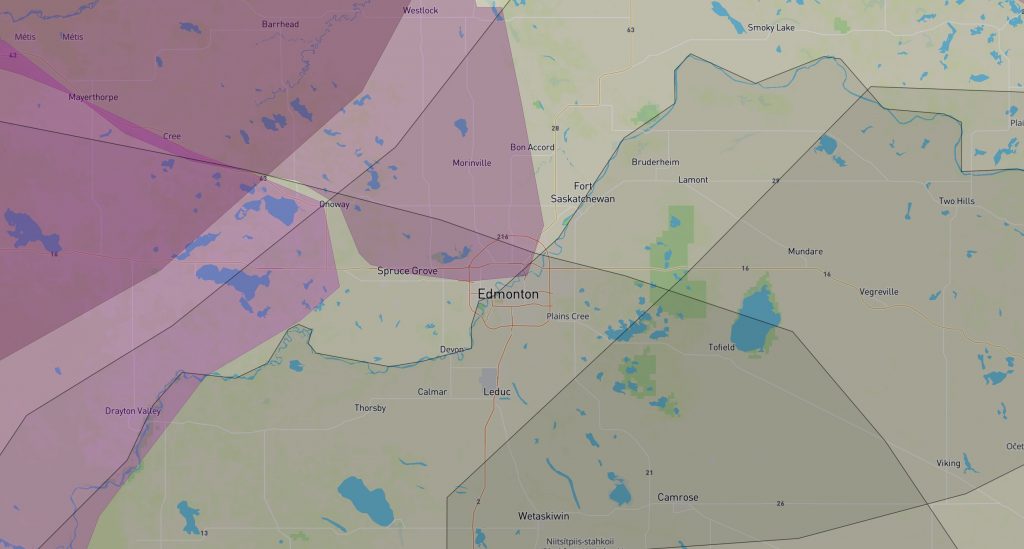

Checking the https://native-land.ca/ site tells me that I’m on the land of:

So there are other names for where I am now, obscured from view. Searching for some more information about Indigenous place names throws up an interesting 2017 article about putting some Indigenous place names (back) onto the map:

“Indigenous place names reveal information about the area’s geography, history and sometimes ecology. Names connect the land to the culture, while acknowledging the contributions of Indigenous people. Not recognizing those contributions — and even actively repressing them — has been a problem for decades.”

The City of Edmonton also has an open data portal and one of the data sets available is an Indigenous Places Names of Edmonton data set. This data set has been visualised as a map (oh, I am very fond of open data visualised as maps – it can be very powerful) which helps me locate some of these places since I am very new to the physical geography of this place.

The Native Land site also tells me that I’m on Treaty 6 territory (and I see people use this as their Location in Twitter regularly too).

“Treaty 6 is the sixth of seven numbered treaties that were signed by the Canadian Crown and various First Nations between 1871 and 1877. Specifically, Treaty 6 is an agreement between the Crown and the Plains and Woods Cree, Assiniboine, and other band governments at Fort Carlton and Fort Pitt. ”

“Since Treaty 6 has been signed, there have been many claims over miscommunication of the treaty terms from the Indigenous and the Crown’s perspective. This misunderstanding has led to disagreements between the Indigenous peoples and the government over the different interpretations of the treaty terms” (Treaty 6, Wikipedia)

I took my eldest niece to the National Library in Wellington a few years ago to see the Waitangi Treaty exhibition and so this is a story somewhat familiar to me in it’s broad brushstokes at least. Radically different ideas about land ownership and poor / difficult translation between parties seems to be a recurring trope of the colonial project. An email about research activities here at Athabasca University recently caught my eye, and led me to the work of Sheldon Krasowski, who published in 2019 his research on the history of the treaty negotiations.

“The most controversial aspect of the treaties is the surrender clause. The treaty text states that the Indigenous peoples “do hereby cede, release, surrender, and yield up” all of their lands to Her Majesty the Queen. However, my research has shown that a close analysis of eyewitness accounts reveals that the surrender of lands was never discussed during the treaty negotiations. ” (Opinion: To understand why the land remains Indigenous, look to history, Globe and Mail)

This all leaves me still pondering the difficult question of where I am and how to name it. There is no easy resolution here and so the best I can do is to hold all these different places in mind at once. Certainly none of this fits into the tyranny of a neat one line box for Location.

* “The deletions included acorn, adder, ash, beech, bluebell, buttercup, catkin, conker, cowslip, cygnet, dandelion, fern, hazel, heather, heron, ivy, kingfisher, lark, mistletoe, nectar, newt, otter, pasture and willow. The words introduced to the new edition included attachment, block-graph, blog, broadband, bullet-point, celebrity, chatroom, committee, cut-and-paste, MP3 player and voice-mail.”

You’ve seemingly landed well and curious and having done this myself from different routes, it’s a lot of betwixt and between. I’ve got mixed locations myself, but maybe the idea of having one place is a modern artifact.

It’s hard to fathom even the deeper past, ones of evolving animals, climates that have left no name and the barest of traces. Or even if it was human culture, there’s more we don’t know than we can guess. I always liked the concept from before where I lived in Arizona there were people so old they only had the name of “Ancient Ones”— or that the later people had the obvious name in their language for themselves— “The People” as if there were no others.

Lots to be said for names (and lamenting the demise of bluebells and dandelions for “blog” and “mp3 player”

I always appreciate the references you draw from in these posts.

Waving from Treaty 4 land….

Hi Alan – thanks as always for your comments and kind words. You’ve reminded me that as well as place names, my sense of time here is all out of whack. Where I lived in Scotland I was steeped in history that was visible and understandable to me. Linlithgow and the lochside walk I did regularly is the birthplace of Mary, Queen of Scots. The ruined palace there is her birthplace. Nearby is also Cairnpapple Hill, which I often posted the view from. Up there is a neolithic henge and a bronze-age burial cairn. Ancient history of people we don’t have names for, but who’s mark on the landscape is still very visible. Here I don’ t know how to read the signs and signals and it seems like there’s been a systematic eradication of such information to make it even harder. I feel very adrift in an unfamiliar landscape.

Hi Ann-Marie

Great to have you arrive,in the frozen north, and after a few weeks you write this introspective review of “where am I?” This is an exercise we ought to require (as a society), from middle school to high school to entry into post-sec to grad school candidates, and for starting any job, whether that be as an accountant or a service worker or a health practitioner – all livelihoods. Your “where am I” begins the conversation in exploring the history and identification of what we blithely call the “land acknowledgement” at the beginning of so many meetings and events, where there is less historical knowledge and curiosity imparted, than what our intrepid newcomer-to-Canada has already identified – that we are a settler and immigrant society with a deep requirement to acknowledge, understand, and act upon the Indigenous rights and origins of this land.

Welcome, again! I wave to you from Sḵwx̱wú7mesh territory.

Vivian