This is the full text of the paper that Karoline and I wrote for the QAA Enhancement Themes 2018 conference and presented on 7 June.

Lecture Recording: A student co-creation case study

Anne-Marie Scott, Karoline Nanfeldt. University of Edinburgh.

Abstract

The University of Edinburgh has been using lecture recording at a modest scale for nearly a decade and it has been exceptionally popular with students. Lecture recording has always been understood as a supplemental resource to aid revision, adding richness to our digital collections.

Students Association officers were elected in each of the 2012 – 2016 elections with lecture recording as part of their manifesto. At the 2016 election, lecture recording was in the manifestos of 3 out of 4 winning candidates. A 2015 external report on the student digital experience identified lecture recording as a significant missing component. Widely available, centrally provided lecture recording was also one of the main recommendations from the 2016 review of the University Accessible and Inclusive Learning Policy. In response to this demand to increase the use of lecture recording, we began a 3 year programme to rollout a new service to 400 teaching spaces in September 2016. The first phase launched in September 2017.

This case study describes our lecture recording programme, highlighting the response to student demand. We will cover how the project has gone beyond consultation, including students as active co-creators of the new service working with staff as colleagues from the procurement stage onwards. We will discuss the benefits for the institution and for students of taking this approach.

Introduction

Lecture recording has become a widespread and pervasive component of technology enhanced learning within Universities and is often understood to be an inherently student-focused part of the digital education portfolio. Lecturing typically remains one of the few high-stakes activities within the institution; if a student is ill or otherwise unable to attend, there is often no alternative provision. By 2016 every Russell Group University except Edinburgh had a mature centrally supported lecture recording service and many of the implementations of lecture recording within comparator institutions were in direct response to student demand: Students petitioned the University of Leeds in 2014; lecture recording was the number 1 service requested by students at the University of Oxford; and the University of Newcastle implemented lecture recording as a direct response to concerns about charging students fees.

At the University of Edinburgh, student demand for lecture recording came in a number of forms:

- Students Association officers were elected in each of the 2012 – 2016 elections with lecture recording as part of their manifesto. At the 2016 election, lecture recording was in the manifestos of 3 out of 4 winning candidates.

- In the data collected as part of the 2013 business case for refreshing our media asset management facilities, lecture recording was the number one requested media technology from Edinburgh students.

- A 2015 report from external consultants (Headscape) on the Edinburgh student digital experience identified lecture recording as a significant missing component from the student perspective. High demand for lecture recording was linked to expectations about the experience at a globally-ranked University, and anxiety about coping with workload stress and illness.

- Investment in an opt-out centrally provided lecture recording solution was one of the significant recommendation from the 2016 review of the University Accessible and Inclusive Learning Policy.

- A 2016 survey in the School of Divinity at University of Edinburgh showed that students are accessing lecture recordings for a range of purposes including as part of writing coursework essays and for tutorial preparation. There was a very strong theme of using recordings to augment notes taken in the physical lecture. “I feel as though the lectures are fast paced and I often miss some of the information whilst trying to get to grips with some of the difficult concepts. I hate to miss the lectures, but having the video recordings has made the course far more manageable.”

The University is committed to investing in and improving the student experience and it was recognised that there was a significant risk that we were overlooking a key area that would have positive influence, as well as falling behind our peers. This paper will outline the approach taken to developing a new, centrally-supported lecture recording service at the University of Edinburgh, and highlight the central and active role that students have played in its development.

Student satisfaction and support for learning

Research has shown that the use of recorded lectures as a supplement to face to face learning has a positive effect on student achievement, and has particular benefit for non-native speakers, students with specific disabilities, and students from diverse backgrounds, in addition to the well-being and satisfaction of the student population as a whole. Making it simple to record lectures affords staff opportunities to be innovative and creative within their teaching practice, as well as offering increased flexibility around use of the physical estate. Emerging research in the field of learning analytics is providing exciting insight into how use of media and other online resources support and enhance learning.

Initial results from the 2016 study at the University of Edinburgh by Headscape into “the digital student experience”, found that students had a number of key use cases for lecture recording including:

- Understanding of lectures by students where English is not their first language

- Catching up on lectures they had missed due to illness or other personal issues

- Reviewing of lecture material for understanding, assignments or exam review

Williams and Fardon (2007) studied the impact of lecture recordings on students with disabilities at the University of Western Australia. Lecture recordings can be captioned, supporting not only deaf and hard of hearing students, but those with learning differences. Looking at 130 students with self-reported disabilities, 66% said recordings are an “essential” learning tool. Recordings also help the 25% of students in the study with mobility impairments who could not physically attend class.

Shaw and Molnar (2011) report an overall course performance increase of 6%. They reported that as a proportion of the whole population, non-native English speakers benefitted significantly more.

Leadbeater et al. (2013) report around 50% of a course cohort used recorded lectures, rising to 75% for some specific courses at the University of Birmingham. Student use of recorded materials was targeted and strategic, with some choosing to use small sections to revise specific concepts, whereas others played back the entire lecture. Of those replaying the whole lecture a very high proportion were dyslexic or non-native speakers of English.

Project Overview

At the start of 2016, we had around 35 rooms enabled for automated, centrally managed lecture recording. However, our system was 8 years old, beyond end of life, and would need to close completely after academic year 2016/17. Due to the declining reliability of the central lecture recording service, the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Science had invested in their own solution and purchased the Panopto system. In academic year 15/16 the Panopto license was extended to allow other Colleges to pilot the system. However, license fees, local IT support, a hard requirement to use the Learn VLE, and no automated recording was proving to be a barrier to participation. There was strong demand from all 3 Colleges for a single centrally supported system to meet student expectations.

Using the evidence of sustained student demand, combined with research outlining significant benefits for many key groups of students, we successfully bid for funding, and initiated a 3-year project to roll out lecture recording into around 400 teaching spaces.

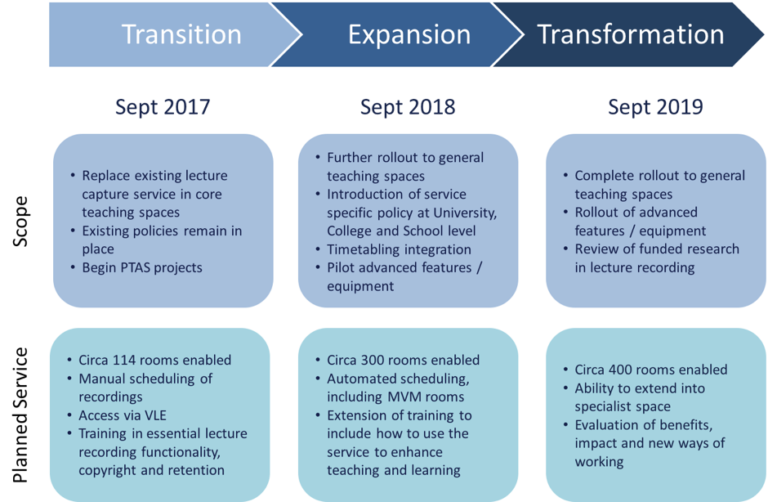

Figure 1: Overview of the 3-year Lecture Recording Programme

The following project objectives were identified within the business case used to secure funding, ensuring that student needs were foregrounded from the start:

- Enhance student satisfaction with learning resources and academic support by automating the recording of lectures at scale across the institution and making them available to supplement face-to-face teaching.

- Reduce the risks around lecturing as a high-stakes activity, in particular supporting student well-being and reducing stress.

- Support the recruitment of international students for whom English is not their first language.

- Support the learning of students with specific disabilities.

- Support pedagogical innovation by enabling staff to record their lectures and use contact time for other activities (flipped classroom).

- Support sustainability and creativity through growing a repository of high quality recorded lectures that can be shared, re-used and re-mixed as appropriate.

- Support sustainability and simplification by delivering a solution within centrally managed teaching spaces that can be extended into locally managed teaching spaces through a ‘buy-in’ option.

- Enable more flexible use of the physical estate as lecture delivery will not be limited by physical room size.

- Create new opportunities for research, particularly in relation to learning analytics and teaching at scale.

Students as Co-Creators

There are many examples of students working as co-producers of knowledge and curriculum within Universities. Within this project we made a deliberate decision to go beyond consultation and incorporated students as active participants in the co-creation of the new lecture recording service via a number of routes.

Procurement

As there were a number of options available to us in terms of lecture recording technology, we used the competitive dialogue procurement process. Competitive dialogue involves a pre-qualification stage, after which successful suppliers work through rounds of dialogue with the institutional team to explore how their product might best fit needs and then finally respond to a very tightly defined Invitation to Tender process.

We made a conscious decision to include students within the competitive dialogue team and through our Students Association, recruited 2 representatives. This was an entirely voluntary activity and in practice only the School convenor from the School of Philosophy, Psychology & Language Sciences was able to participate.

From the start our student representative was a full member of the procurement team and was in the room with suppliers, quizzing them on how their solution best met student learning needs, and helping to draft the Invitation to Tender. This was a novel, but not unwelcome experience for suppliers, and her input directly influenced both the weightings and questions in the final Invitation to Tender document particularly where features of the product or services on offer related to the student experience. She also negotiated with the institutional team during the consensus stage of scoring the ITT, again arguing in favour of elements felt to benefit the student experience.

Student Internships

After the procurement had been successfully completed, we employed 2 student interns on 12-week long summer placements to help deliver the service. One of these was the intern who had helped us with the procurement phase. As we worked towards the first service launch in September 2017, interns working as part of the implementation team undertook the following activities:

- Interviewed academic colleagues and developed a series of short videos on the benefits of lecture recording

- Wrote a post for our Teaching Matters blog on lecture recording and attendance

- Delivered face to face training for academic staff on accessibility, copyright and using open resources in lecture materials

- Supported the delivery of the wider training programme via admin support

- Attended various academic user groups to present the student perspective on the project

- Designed merchandise, including sourcing from suppliers (t-shirts, pens, card wallets)

- Developed student-facing communications materials, including a flyer to go in Welcome Week materials

- Installed signage and helped commission the first 138 rooms for first launch

- Helped to recruit, train and supervise student helpers over the start of term launch period

We subsequently kept 1 intern on for a further 9 months on a part-time placement to continue to deliver training, communications assistance and to evaluate the student helper scheme.

Students as the face of the service

In order to support the first 2 weeks of the live service, we also recruited and trained around 30 student helpers. These students were the public face of the new service as it launched, visiting lecture theatres at the start of teaching and directing academic colleagues quickly towards support where it was required.

The student helpers were instructed not to provide technical support. In the eventuality of any issues, they were asked to contact our Helpline with the issue. At first they were asked to hang back, but in the first few days, it became clear that it worked better if they said hello to the academic, and thereafter left if they were not needed. Student helpers were surveyed as part of the activity evaluation, and it is clear that they would have liked more training on how to use the system and would like to provide basic technical support on-site, especially to do an ad-hoc recording. Student helpers found that some lecturers became interested in doing an ad-hoc recording because they were there.

Impact

The impact of this project has been significant. In terms of meeting student expectations and demands, although there continues to be pressure to scale up the use of lecture recording and move swiftly to an opt-out model there was no mention of lecture recording in any of the Students Association 2018 election literature, suggesting that it is no longer an active campaigning issue. Initial evaluation activities are also highlighting that some of the benefits for key groups of students are being realised:

“The recorded lectures have been amazing for me. I just listened if I was at the lecture, and then made notes on them while watching them at home. Seeing the lecturer is even better than audio. I have problems doing handwriting for extended periods. As a carer I have to drive frequently on a one hour commute […], and listening to the audio of the lecture in my car reduced my stress because I really felt I was making good use of the time for my studies as well as doing my family duty.”

There was already strong direction from our Chief Information Officer towards offering student employment opportunities, however there is now a push towards having student interns participate actively in all major student-facing projects. This summer we will be employing a new intern to continue to work with us on lecture recording, and a new intern to support the implementation and rollout of an academic blogging service. 3 new interns have also now joined our Digital Skills team to deliver training and we are considering an intern to support our Wikimedian in Residence.

In general, our Information Services Group is being seen positively by students as a place to work, and the opportunity to shape the services they use is highly valued. Students who have been involved in internships with us on this project continue to want to be involved in other aspects of our work. One intern is actively looking to pursue a career as a learning technologist upon graduation and another has gotten involved with our Wikipedia work, running their own edit-athon in the School of Law.

Colleagues impressions of what student interns can do, and the standard of work they can produce has been also been improved. There is a greater awareness of the role that students can play and the experience that they can bring. Student interns are often canvassed as trusted colleagues for their views on a wide variety of activities within Information Services Group.

The student helpers scheme for the start of term is being considered for expansion to support the rollout of Windows 10 across campus, and in the Vet School it has led to students proactively asking to set up an ongoing IT help scheme.

Our students have also been recognised beyond the institution, with our longest serving student intern being asked to participate in 2 cross-institution student panels on lecture recording.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Whilst no individual student can hope to represent the entire student body, we know that diversity in teams makes for better outcomes. More breadth of opinion and experience can spark more innovative thinking about challenges. Employing students will bring their authentic experience of being a student right now, and can avoid defaulting to any lazy stereotypes. In short having students in the room will make us all better and will ensure that the services that we develop are genuinely built with students needs in mind. With that in mind, we would offer the following three recommendations for any projects looking to take a similar approach:

- Employ students

The benefits for students and ourselves are significant. Our students are keen, enthusiastic, hard-working and usually very committed to the institution. Employing students is an opportunity to offer meaningful work experience and at the same time benefit from their fresh perspective. If the institution offers understanding and a bit of flexibility when it comes to working hours during term-time, part-time employment can also work very well with a student’s studies.

- Don’t underestimate students

Student colleagues may question or challenge our systems or the way we work. Embrace those challenges, be prepared to think critically about whether things need to be the way they are. Offer genuine opportunities to students to play significant hands-on roles in shaping the services that they use, particularly where those services are designed to enhance their student experience. Make sure that students feel valued and part of the team – a major part of getting the most of a student’s potential is to ensure they feel like they can voice their opinion and that their contributions matter.

- Engage with a diverse group of students where possible

Use students to engage with the wider student body. No matter a student’s background, they share the experience of being students at the same University, which can create a shared sense of understanding.

References

Leadbeater, W. Shuttleworth, T. Couperthwaite, J. Nightingale, K.P. (2013). Evaluating the use and impact of lecture recording in undergraduates: Evidence for distinct approaches by different groups of students, Computers & Education, 61: 185-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.09.011.

Shaw, G. P. and Molnar, D. (2011). Non‐native english language speakers benefit most from the use of lecture capture in medical school. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ., 39: 416-420. doi:10.1002/bmb.20552

Williams, J. & Fardon, M. (2007). Perpetual connectivity: Lecture recordings and portable media players. In ICT: Providing choices for learners and learning. Proceedings Ascilite Singapore 2007. http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/singapore07/procs/williams-jo.pdf

Also here are the slides we used to present from.

[slideshare id=102644869&doc=2-180619092640]